When heavy fighting erupted in Sudan in April 2023, it didn’t only drive families from their homes, it also emptied out the nation’s classrooms. In the ensuing chaos, education came to a standstill. As of late 2023, over 10,400 schools have been forced to close in conflict-affected areas. The new academic year began with virtually all schools nationwide shuttered, leaving an estimated 19 million children without access to education. This staggering figure – roughly 90% of Sudan’s school-age population – makes Sudan’s conflict one of the worst education crises in the world.

Every level of the education system has been affected. Many school buildings in Khartoum, Darfur and Kordofan have been damaged or occupied by armed groups, or repurposed as shelters for displaced people. National exams were cancelled due to the fighting. “This war has spelled the end of education in Sudan, and things have turned from bad to impossible,” one displaced student lamented. Even in regions spared from violence early on, insecurity and uncertainty have kept schools closed. By August 2023, just a few months into the conflict, the number of children out of school had already soared from 6.9 million to 9 million, according to Save the Children. Now, after more than a year of war, almost every child in Sudan is cut off from formal schooling, a situation experts warn risks a “generational catastrophe” for the country.

Millions of Young Learners Uprooted and At Risk

The war’s toll on children goes beyond missing classes, it has upended their entire lives. Conflict between the army and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) has driven massive displacement, with over 4 million people fleeing their homes within Sudan and across its borders. This includes millions of children who have been uprooted from their communities and schools. By late 2023, around 2.5 million children were newly displaced inside Sudan due to the fighting. Many families have fled Khartoum and Darfur to safer states or neighboring countries; in all, Sudan now has the highest number of internally displaced children in the world at roughly 3.5 million. Refugee camps in Chad, South Sudan, Egypt and other countries are swelling with Sudanese children in need of schooling. But resources are strained, for instance, in Chad (host to over 370,000 Sudanese refugees), formal education options for new arrivals are extremely limited.

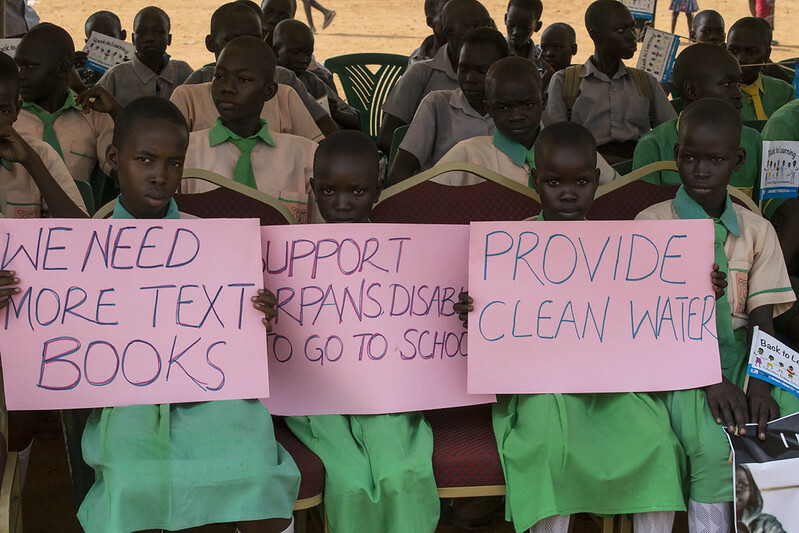

“Launch of second phase of Back to Learning initiative in South Sudan” by UNMISS, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Being out of school also means loss of protection and routine for these children. Schools in normal times offer not just learning but a safe haven providing meals, healthcare, and stability. Now, countless Sudanese kids are living in crowded camps or unfamiliar communities without those supports. Humanitarian reports warn that children out of school face greater dangers: they are more susceptible to child labor, early marriage, recruitment by armed groups, and other forms of exploitation. “Children have been exposed to the horrors of war for nearly half a year. Now, forced away from their classrooms, they are at risk of falling into a void that will threaten the future of an entire generation,” UNICEF’s Sudan representative said mid-conflict. Tragically, there have even been reports of child soldiers and abductions as desperate youths become targets for armed factions. In short, the war has not only interrupted schooling, it has robbed Sudan’s young learners of the safety and structure that school provides.

Foundational Skills and Early Learning Losses

For primary-aged children, missing school is especially damaging. The early elementary years are when students normally master foundational skills like basic reading, writing, and mathematics, skills that underpin all future learning. In Sudan now, those critical lessons are not happening. A whole cohort of first, second, and third graders have spent their formative education years out of the classroom. As a result, experts fear an explosion of learning poverty, the share of children unable to read or do simple math by age 10. If children do not learn to read in the first few grades, their long-term academic prospects plummet, and many may never catch up. Even before the war, learning outcomes in Sudan were worrying: national assessments showed low literacy and numeracy levels by grade 3, and nearly 7 million children were already out of school due to poverty and past instability. Now, with the conflict halting schooling for virtually all young learners, those educational gaps are widening into chasms.

Research on previous school disruptions illustrates the stakes. During the COVID-19 pandemic, for example, extended school closures led to significant learning loss worldwide. One global study found that 25 weeks of missed classes resulted in students losing nearly a full year’s worth of learning, including about one-third of expected progress in reading skills. The war in Sudan has closed schools for far longer than 25 weeks, in many areas, children have lost two consecutive school years. The likely outcome is drastic erosion of foundational skills. Many Sudanese 7- or 8-year-olds who should be reading simple sentences are not literate at all right now; many 9- or 10-year-olds have not learned basic addition or subtraction. As UNICEF notes, beyond academics, school also teaches social and emotional skills which help children cope with trauma. Those coping mechanisms and routines have been stripped away, leaving children isolated in a state of toxic stress.

Alarmingly, economists estimate that the long-term cost of these learning losses will be enormous. A recent analysis projected that if Sudan’s out-of-school crisis isn’t addressed, it could result in a net lifetime earnings loss of $26 billion for this generation of children . In other words, the war is not only disrupting childhood, it is also undermining the country’s human capital and future workforce. Early-grade learning matters: without urgent intervention, Sudan risks a generation of youth who lack basic literacy, numeracy, and the skills needed to rebuild their lives and nation.

Urgent Actions to Keep Children Learning

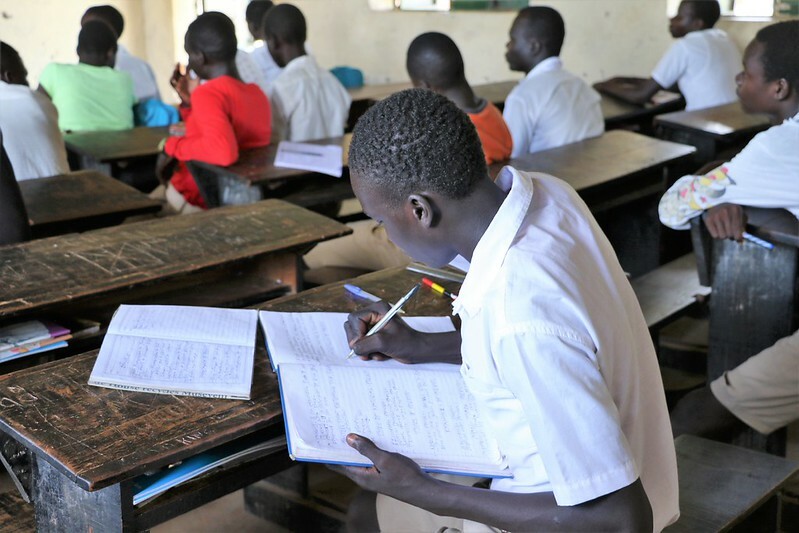

“Girls in South Sudan just want to learn” by EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Humanitarian organizations and Sudanese communities are scrambling to prevent a total collapse of education. Education cannot wait until the war ends, experts emphasize, or an entire generation will be lost. As one education official put it, “During the COVID-19 pandemic, parents in wealthy countries didn’t want children to wait even a month for their education… So why should we expect [children in Sudan] to wait until the conflict is over?”. In this spirit, a range of emergency education initiatives have sprung up: from temporary learning centers to radio lessons and mobile classrooms, all aimed at giving Sudan’s children some continuity in learning.

Children in Sudan receive educational kits in an effort to resume learning amidst conflict. With support from humanitarian organizations, some students are gradually returning to learning in safer areas, even if under makeshift circumstances. For example, in relatively calm states like Blue Nile, UNICEF and partners launched “back-to-learning” campaigns to help enroll displaced children in local schools. At one girls’ school in Blue Nile, enrollment climbed to 500 students (including 120 displaced and refugee children) after a UNICEF-supported drive encouraged families to send kids back to class. In many communities, schools have also become hubs for aid: they double as safe spaces where children can receive meals, counseling, and playtime while catching up on lessons. Education is seen as a lifeline, as critical for children’s well-being as food or medicine. “In the Sudan emergency, education is not a secondary need, it’s lifesaving… without it, children risk losing not only their future, but their present,” says one program manager involved in the response.

Where physical schools remain too dangerous to open, alternative learning modes are being deployed. Aid groups have set up Safe Learning Spaces in displacement camps and host communities, where volunteer teachers lead informal classes and provide psychosocial support. The Sudan Education Cluster (a coordination body of NGOs and U.N. agencies) is prioritizing a mix of solutions tailored to different areas. In active conflict zones, the cluster is providing remote lessons and e-learning resources so children can study from home or shelters. In areas that have stabilized, they are working with local authorities to repair schools, relocate any displaced families using school buildings as shelter, and reopen classrooms as soon as possible. To support these efforts, the U.N.’s global fund for education in emergencies, Education Cannot Wait, quickly raised $12.5 million to finance education services for Sudanese children both inside the country and in refugee settings . These funds are helping deliver things like school-in-a-box kits, teacher stipends, and catch-up curriculum for an initial 120,000 children, a small fraction of those in need, but a critical start.

Even simple interventions can make a difference. Providing displaced kids with basic school supplies, a notebook, a pencil, a textbook, can spark hope and routine. “A child without a pencil is a future without possibilities,” one Sudanese teacher observed, highlighting the importance of learning materials. Likewise, organizing students into informal study groups or safe play areas can help preserve some normalcy. Humanitarians underscore that every additional month a child remains out of school increases the risk they never return . Thus, the collective goal is to keep children engaged and learning by any means available, be it through community classes, radio educational programs, or even storytelling circles, until formal education can fully resume.

Digital and Mobile Learning: A Lifeline Beyond Classrooms

One promising avenue to reach Sudan’s displaced young learners is through digital and mobile learning solutions. Even before this conflict, Sudan had begun experimenting with technology to bring education to remote or out-of-school children. For instance, in early 2023, UNICEF launched a solar-powered e-learning initiative in rural Sudan, equipping community centers with tablets pre-loaded with interactive reading, writing, and math lessons. These tablets, charged by solar panels and usable offline, allowed children with no access to regular schools to continue learning through educational games and videos. Local facilitators were trained to guide the children and monitor their progress, while the content was aligned to Sudan’s national curriculum. Crucially, the digital lessons were designed to be self-paced and child-friendly, using stories and voice-overs to teach basic literacy and numeracy, an approach especially helpful for young learners who may not read yet.

“A smart classroom and laboratory at the school provided as part of Rweru model village during Liberation Day Celebrations – Kwibohora22 l Rweru, 4 July 2016” by Paul Kagame, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Such initiatives have become even more critical during the war. When schools and teachers are not reachable, mobile technology can deliver lessons directly to children. A tablet or smartphone loaded with educational material can serve as a “classroom in a box” for a child sheltering in a camp or distant village. Of course, digital learning is not a cure-all, it depends on devices, charging, and sometimes internet connectivity (which is unreliable in many areas). But in some conflict zones, creative solutions are overcoming these barriers. Humanitarian innovators have used solar-powered projectors to screen video lessons in community centers, distributed lessons via WhatsApp and SMS for families with basic phones, and set up local radio school broadcasts for children with no digital access. During the pandemic and other crises, such low-tech methods proved effective at reaching learners who would otherwise be completely cut off. In Sudan’s current crisis, scaling up these remote-learning tactics could help mitigate learning loss, especially for primary-grade children eager to learn their ABCs and 1-2-3s.

Importantly, any digital solution must be designed for low-resource settings. Sudan’s experience shows that content must be available offline or zero-rated (not consuming mobile data) to be practical. It also helps to involve caregivers or community volunteers to support children’s learning with the devices. As UNICEF noted, “A tablet can never replace a teacher, but in the absence of trained teachers, a digital solution can support the learning of children” by enabling self-learning and practice. In other words, mobile learning can keep the flame of education alive until it’s safe for teachers and students to reunite in person.

A Curriculum to Support Displaced Children

Amid these efforts, educational nonprofits are also stepping up with innovative resources. One example is AHS Education (AHSEdu.org) – a free, mobile-accessible curriculum designed to provide continuous learning for children in crisis or displacement. AHS offers a complete standards-aligned curriculum for Grades 1–5, delivered through interactive video lessons, quizzes, and printable worksheets. Critically, the platform is optimized for disrupted environments: it supports offline use on smartphones or tablets, so students can download lessons when they have connectivity and study anywhere, even without internet. Each lesson is modular and self-contained, allowing children to progress at their own pace and resume learning whenever possible, a key feature for those facing interruptions and relocations.

Because AHS Education is free and open-access, it functions as an “education insurance policy” for vulnerable communities. Schools or NGOs can quickly enroll classes of children and track their progress on a simple dashboard, even if teaching must happen remotely. There are no fees or licenses required, removing barriers for impoverished or rural areas. In essence, platforms like this provide a ready-made solution to keep children learning during emergencies: if a school is destroyed or a family is forced to flee, the child’s education can continue on a phone or tablet without costly infrastructure. For Sudan’s millions of displaced learners, such a resource could be transformational, helping them practice reading and math daily, maintain a sense of routine, and eventually reintegrate into formal schooling with less learning loss.

Humanitarian groups are now exploring how digital curricula like AHS can be integrated into the Sudan education response. Some aid agencies are including pre-loaded learning apps and devices in their emergency education kits. Community tutors and parents are being trained to use these tools so they can support children’s learning in camps or host communities. The goal is to ensure that even if school buildings are closed, “class” can continue in some form. As one Sudanese 10-year-old, recently back in school after two years of disruption, wisely said: “We must go to school even during the war so we can learn and not lose out for years”. To make that possible for all children, every available channel, from traditional humanitarian aid to modern e-learning technology, is being leveraged.

The international community must recognize education as a front-line necessity in Sudan’s crisis. Supporting initiatives that deliver learning in conflict zones is an investment in peace and a future for Sudan’s youth. Tools like AHS Education’s curriculum are available for NGOs and schools to deploy immediately in disrupted areas. (For example, see AHS Education’s demos for institutes, and non-profits, to understand how a free mobile curriculum can be used in the field.) By expanding such programs and funding local educators, we can help Sudan’s “lost generation” of young learners regain their education, and with it, hope for a better tomorrow.

AHSEDU.org offers personalized learning for every student. With a curriculum standardized with USA State Standards, Free interactive videos, Fun and interactive learning content, Constructive assessments, and take-home worksheets we address the unique educational needs of each learner to ensure success.